Zura Karuhimbi had no weapons to defend herself when the men waving machetes surrounded her home, demanding she hand over those she was sheltering inside.

She did, however, have a reputation for magical powers.

That reputation, and the fear it engendered in the group of heavily armed men, was enough to keep an elderly woman and more than 100 others safe during the Rwandan genocide.

Some 800,000 other Tutsis and moderate Hutus would die in the ethnic violence which engulfed Rwanda in 1994 - including her first-born son and a daughter.

"During the genocide, I saw the darkness of a man's heart," she would tell The East African two decades later from the same tiny, two-room house she hid so many people inside.

Born to a family of traditional healers

Karuhimbi died peacefully at home in Musamo Village, about an hour east of Rwanda's capital, Kigali, on Monday. No-one is entirely sure how old she was.

By her own account, she may well have been well over 100. Official documents suggest she was closer to 93.

Either way, when the Hutu militias - known as the Interahamwe - arrived in her village, she was not a young woman.

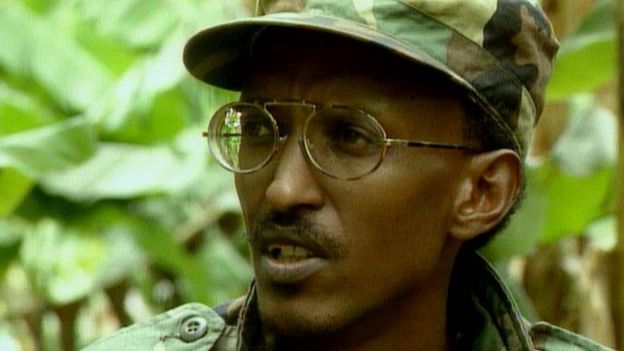

Hutu militiamen run through the streets with French soldiers in June 1994

Hutu militiamen run through the streets with French soldiers in June 1994

Karuhimbi was, according to the numerous stories written about her life, born to a family of traditional healers in about 1925. The year comes courtesy of an official identity card.

It could be argued that her path towards the events of 1994 was set in motion when she was still just a child. It was then the Belgians decided to take the population of Rwanda, and split them into clearly demarcated groups - complete with identity cards, laying out whether they were Hutu or Tutsi.

Karuhimbi's family were Hutu, the group which made up the majority of Rwanda's population. The minority Tutsis were considered superior, and for this reason, given access to better jobs and educational opportunities by the colonialists.

The division fuelled tensions between the two groups: Karuhimbi was still young in 1959, when Tutsi King Kigeri V, together with tens of thousands of Tutsis, were forced into exile in neighbouring Uganda following what was referred to as a Hutu revolution in Rwanda.

So, when the first attacks began in the days which followed the downing of Hutu President Juvenal Habyarimana's plane in April 1994, it was not the first time she had seen such violence.

But she could not have known how bad things would get, as Hutu husbands began to turn on their Tutsi wives in order to avoid the same fate.

Even if she did, one suspects it wouldn't have stopped her.

"I used to say, 'If they die, I will also die,'" she told the Kigali Genocide Memorial.

'Digging their own graves'

The little two-room house in Musamo Village quickly became a safe haven for Tutsis, Burundians and even three Europeans during the genocide. Dozens of people reportedly hid under her bed and in a secret space in the roof. Others say she dug a hole in her fields where people hid.

Some of those concealed on the property were babies, taken from the back of their dead mothers, she would say.

Much like her age, no-one really knows how many people there were in the house: it wasn't like she was counting, Karuhimbi told Rwandan reporter Jean Pierre Bucyensenge on the 20th anniversary of the genocide. At the time, she had far more pressing things to deal with.

It was enough people, however, to alert the Hutu militia.

"Zura's only weapon was to scare the killers that she would unleash spirits on to them and their families," Mr Bucyensenge explained. "She would also anoint herself with a local skin-irritating herb and could touch the killers to try to keep them away."

It was a method remembered clearly by Hassan Habiyakare, one of the people the feared "witch" saved.

"Zura told Interahamwe militia if they entered the shrine, they would incur the wrath of Nyabingi [a Kinyarwanda word for God]. They were frightened and our lives were saved for another day," he recalled.

"If they are to die, i die with them" - Sula Karuhimbi #Ubumuntu #ChampionHumanity #RIP pic.twitter.com/KPNLv1EB7G

— Kigali Genocide Memorial (@Kigali_Memorial) December 18, 2018

Karuhimbi herself would tell how she would shake her bracelets and anything else she could find in order to scare the men away.

"I remember one Saturday, they came back again," she told The East African in 2014. "I confronted them as usual, warning them that by killing the refugees in my house, they were digging their own graves."

The warnings worked. When the genocide ended in July, as Tutsi-led rebels entered Kigali, every single one of the people Karuhimbi had risked her life to save had survived.

Life carried on as well as it could. She was a mother in mourning, having lost a son to the violence, and a daughter she later said had been poisoned.

And the legend of the witch of Musamo Village continued, despite her repeated assertions that she was not, and had never been, a witch.

"I only believed in one God and the thing of magical power was just an invention and cover I was using to save lives," she told Mr Bucyensenge in 2014.

"I am not a witchdoctor."

The tale, however, reached the highest levels in Rwanda, and, in 2006, she was awarded the Campaign Against Genocide Medal. It gave her the chance to share another tale of a life she had saved almost 50 years earlier.

Medal stashed under pillow

According to Karuhimbi, on that occasion in 1959 - as inter-ethnic violence was escalating between the two groups - she advised the mother of a two-year-old Tutsi to take the beads from her own necklace and tied them in a little boy's hair.

Zura Karuhimbi kept her medal close at all times

Zura Karuhimbi kept her medal close at all times"I told her to carry her son and not put him down, so the militia would think he looked like a girl when they saw him, because they only killed boys at that time," she told news outlet Vice.

That boy, she said, survived - and went on to become the man who presented her with the medal, President Paul Kagame.

Karuhimbi never really knew what happened to any of the other people she helped. Her final years were spent being cared for by a niece, as far as it known.

In her last newspaper interviews, she was still living in the house, but poverty meant it was starting to crumble around her.

The medal Mr Kagame handed her in 2006 remained a treasured possession. She wore it at all times, stashing it under her pillow for safekeeping when she slept.

And now those who met her hope that the story of the Hutu woman who gave everything for others during those terrifying days will travel far beyond the borders of her village.

"She risked her life to save others," Mr Bucyensenge told the BBC. "And to do that, she only had to improvise: she faced armed gangs with her full body and intellect and she won.

"Her story is a reminder that humanity prevails - even in the most difficult situations."

Source: BBC

Comments