Many refugees relocated to the small Baltic states by the EU face alienation and poverty and end up moving elsewhere in Europe.

It is a headache for the EU, already embroiled in a bitter dispute with Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary over their refusal to accept refugees.

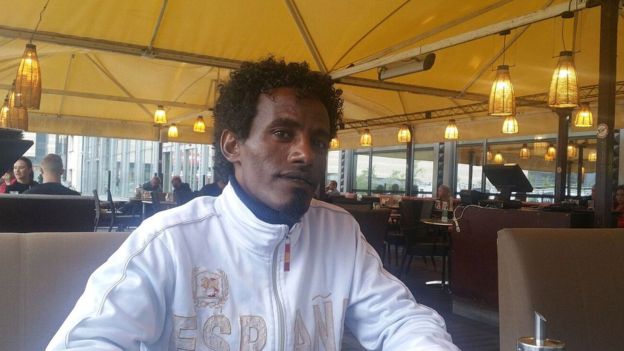

Mekharena, an Eritrean, came to Latvia from Italy a year ago. Reaching Europe was an odyssey - he came via Uganda, Ethiopia, Israel and Egypt.

'They don't give us anything'

He only learnt he was going to Latvia a day before his flight. He was not allowed to choose the destination himself, and was not happy about it.

"There are lots of Eritreans everywhere in Europe. They talk to one another. We all know that in Germany they give you an apartment and €400 (£439; $568) pocket money. But in Latvia they don't give us anything - just €139 a month," he told BBC Russian.

In Riga it is hard to find a one-room flat to rent for that money. But there are no plans to increase benefits.

"Those are our allowances and we can't afford to pay people more - we aren't that kind of country," said Ainars Latkovskis, head of the Parliamentary Commission for Internal Affairs.

"They can of course look for work. But by Latvian law you have to speak the language to get a proper job and it usually takes years to learn," he said.

Mekharena says it is the low living standard that makes refugees leave Latvia as soon as they get their papers. He knows many asylum seekers who have done exactly that.

"Most of them couldn't survive here. They can't accept the difference [between incomes in Latvia and Germany]. Lots of them borrowed money to get to Europe and they need to pay it back," said Mekharena. He himself paid people smugglers $3,000.

Read more on Europe's migration crisis:

Migrant talks as Italy eyes port closures

EU targets countries not taking refugees

Hungary to detain all asylum seekers

Eritrean migrants face new asylum battle

An EU solidarity plan, agreed in 2015, envisaged relocating 160,000 Syrian and Eritrean refugees throughout the EU, from overcrowded camps in Greece and Italy. Only a fraction have left the camps so far.

Politicians here shrug off the onward migration of refugees from Latvia. "We live in a free country, not in Russia. The problem is the war and the terrible situation in Syria. That needs to be resolved," Mr Latkovskis said.

Refugees are moving on from all three Baltic states - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

Of 349 asylum seekers taken in by Lithuania, 248 left as soon as they had received official refugee status, according to Robertas Mikulenas, director of a reception centre in Rukla, a small Lithuanian town.

Benefits for refugees in Lithuania vary from €102 to €204 a month.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

So far 317 refugees allocated to Latvia have arrived in the country, but no office has records of their whereabouts. The fact that none are using the mentoring services available to those with official refugee status suggests they have left.

In Estonia the situation is similar: of the 136 who arrived on the EU programme, 79 have moved elsewhere in Europe. Refugees in Estonia receive €130 a month.

Once granted asylum, a refugee can travel freely within the EU and join friends and family in Western Europe - and the Baltic countries have fulfilled their obligations under the EU quota scheme.

| Plan to relocate 160,000 refugees | (EU data, 29 June 2017) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number accepted so far | Total commitment | |

| Belgium | 745 | 3,812 |

| Estonia | 136 | 329 |

| Finland | 1,739 | 2,078 |

| France | 3,779 | 19,714 |

| Germany | 6,400 | 27,536 |

| Ireland | 459 | 600 |

| Latvia | 317 | 481 |

| Lithuania | 324 | 671 |

| Netherlands | 2,056 | 5,947 |

Nationalist backlash

Many in the Baltics, especially nationalists, support the refusal of Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary to house refugees.

Twenty-three Latvian MPs signed a letter urging the European Commission not to impose sanctions on the three refusenik countries.

One signatory, Karlis Kreslins of the right-wing National Alliance, was dismissive of Latvia's refugees.

"They don't stay long in Latvia, almost all of them left. That means they were just looking for a better life," he said.

Image copyright AFP

Image copyright AFP

Mekharena has been in Latvia for almost a year. Friends are still helping him to pay the rent and now he hopes to find a job.

"I have a higher degree in engineering, but I'll be doing manual labour on a building site. I hope it will work out," he says.

He would like to join his family in London, but is in no rush to go as he does not think he will be able to find a job legally outside Latvia.

"If I move to another country, they won't accept me. I know several people who left Latvia. They all went to Germany but none of them can work there," says Mekharena.

Refugee status in Latvia only gives you the right to claim benefits or work in Latvia. It does not guarantee anything in other EU countries.

According to Mekharena, the refugees who leave Latvia "wait for half a year to submit their applications again, but they are dependent on their friends for help - it's just a waste of time".

So they come back to the same problems they left behind: meagre benefits, they do not speak the language and they struggle to find a job and a place to live.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants

BBC

Comments