Ground-breaking work on synthetic organ transplants made Paolo Macchiarini one of the most famous doctors in the world. But some of his academic research is now seen as misleading, and most of the patients who received his revolutionary treatment have died. What went wrong?

In July 2011, the world was told about a sensational medical breakthrough that had taken place in Stockholm, Sweden. The Italian surgeon Paolo Macchiarini had performed the world's first synthetic organ transplant, replacing a patient's trachea, or windpipe, with a plastic tube.

The operation promised to reshape organ transplantation. No longer would patients have to wait for a donor organ, only to run the risk of biological rejection. Plastic tracheas - and possibly other organs - would be produced quickly, safely, and made-to-measure for each patient.

It was a story that befitted the reputation of Dr Macchiarini's workplace, the prestigious Karolinska Institute, whose professors decide each year who will receive the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

But five years on, Macchiarini's headline-making work has brought KI and its sister organisation, the Karolinska University Hospital, no glory. Of the nine patients that received the treatment, in Sweden and elsewhere, seven have died. The two still alive have had their synthetic tracheas removed and replaced with a windpipe from a donor.

Last week, an independent report sharply criticised the three synthetic trachea operations that took place at Karolinska University Hospital.

The investigation, led by Kjell Asplund, Chairman of the Swedish Council on Medical Ethics, found that the scientific foundation for the new operation was weak, and condemned the failure to carry out risk analyses before the patients received their operations, or seek the necessary ethical approval.

On Monday, a separate investigation at KI identified mistakes made when Macchiarini was recruited and when allegations of misconduct were made against him two years ago.

In the picture that emerges from these reports, we see a doctor persisting with a technique that showed few signs of working and able to take extraordinary risks with his patients, and a medical institution so attached to their star doctor that they ignore mounting evidence of his poor judgement.

Image copyrightSTAFFAN LARSSON

Image copyrightSTAFFAN LARSSON

Not only was Macchiarini known as a brilliant surgeon, he was handsome and impressive - able to give press conferences in several languages.

At the hospital, a "bandwagon effect" emerged around his work. "Regenerative medicine" was at the cutting edge of scientific fashion, and few colleagues raised questions or objections about the basic science underlying the procedures.

The patient who received that first synthetic organ transplant, in 2011, was 36-year-old Andemariam Beyene, a graduate student from Eritrea living in Iceland. After unsuccessful treatment for a rare form of cancer, he had been referred by his Icelandic doctors to the experts at Karolinska University Hospital.

Macchiarini told Beyene that the revolutionary surgery was his only chance of survival and persuaded him to agree to the new procedure.

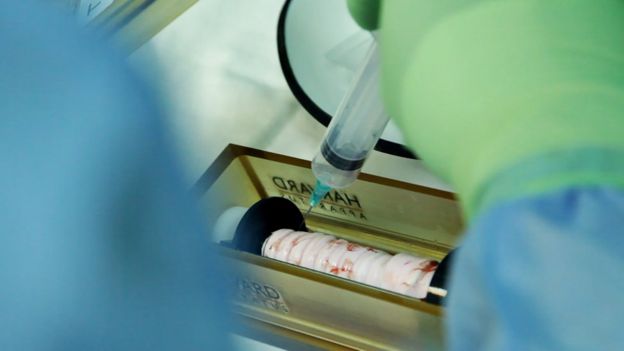

The synthetic "scaffold" for Beyene's new trachea was made in a lab in London. It was seeded with stem cells taken from the patient's bone marrow, then placed in a shoe-box sized machine called a bioreactor, where it rotated in a solution designed to encourage cell growth.

Image copyrightCONAN FITZPATRICK

Image copyrightCONAN FITZPATRICK

Image copyrightCONAN FITZPATRICK

Image copyrightCONAN FITZPATRICK

A month after the operation, reporters from around the world were able to interview Beyene in bed. He told the BBC: "I was very scared, very scared about the operation. But it was live or die."

By the end of the year, Macchiarini and his colleagues were writing in the Lancet that Beyene had an "almost normal airway" that was free of infection and growing new tissue.

The publication of this sent a signal to the medical community that the miraculous-sounding project of growing and implanting synthetic transplants was a viable treatment.

By this time, two more synthetic tracheas had been implanted. In the first - an operation not overseen by Macchiarini - a young British woman in a serious condition received a trachea at University College London. In the second, Macchiarini himself fitted a 30-year-old American man with a new kind of scaffold.

These two patients only survived for a few months. No autopsy was performed on the American man so his exact cause of death is unknown, but we know that the British woman's synthetic trachea did not function well.

Image copyrightUNIVERSITY OF ICELAND

Image copyrightUNIVERSITY OF ICELAND

"At those junctions it always seems to be loose and healing tissue can become an obstruction to breathing.

"The second thing that seemed to happen was that you are putting the trachea on to a bed, which is made up of the oesophagus, the swallowing tube, and the synthetic material could press into the oesophagus.

"Finally, the lining didn't seem to grow into the scaffolds either, so you are left with something chronically infected and unable to clear mucus properly."

The patient was able to go home after the operation, but died two months later.

Over the next three years, Macchiarini implanted six more synthetic tracheas, and four of these patients died. It is unknown whether their deaths were all related to the tracheas, or whether they were due to underlying illnesses or even unrelated events.

Karolinska University Hospital stopped Macchiarini's work in November 2013, but he continued to perform the transplants as part of a clinical trial in Russia.

Meanwhile, reports about the health of the first patient, Andemariam Beyene, remained positive. In a 2014 article published in the Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, Macchiarini reported that he had an "almost normal" airway a year after the operation, repeating the phrase from the Lancet article.

But by the time that article appeared Beyene too had died. He had suffered repeated infections, and his trachea needed to be held open by a series of stents. His autopsy revealed the synthetic trachea had come loose.

The nine synthetic trachea patients

Image copyrightSVT

Image copyrightSVTBBC

Comments